A friend comparing kale varieties

This particular plant family is one of the most versatile and varied in the human food system, and I absolutely love it. They are excellent vegetables for colder climates, and they make great additions to food forests!

I apologize in advance for only having photos of a few different brassicas, I need to get better about keeping visual records of everything I grow.

I struggled to find the best way to title this article since it’s so broad but specific at the same time. But I need to start somewhere so here’s an intro to brassicas!

Plant Profile:

Scientific Name: B. oleracea, B. rapa, B. juncea, and various other species

Edible Parts: Stems, leaves, flowers, buds

Distribution: Nearly worldwide

Harvest Season: Varies

Key Identifiers: Brassicas have a few main identifying marks that once familiar to you they will be almost universally recognizable: Small yellow or white flowers with four petals in a cross shape, lobed, toothed, and or deeply veined leaves, stalks tend to have distinct ridges or the texture of broccoli stems.

Toxic Look-Alikes: There are a handful of plants that can be mistaken for brassicas in the wild, but once familiar with wild mustards you should be able to identify them without issue.

Nutrition:

Brassica species are very dense with many vitamins (A, C, and K in particular), antioxidants, and minerals which makes them great for general health and well-being. Specific medicinal uses vary by species and variety.

So, what are brassicas?

Brassicas are any member of the family Brassicaceae (Brass-i-case-ee-eye). This includes mustard greens, cabbage, rapeseed, broccoli, cauliflower, Brussel sprouts, kale, collard greens, mizuna, tatsoi, Bok choy, napa cabbage, turnip, rutabaga, Romanesco, and kohlrabi among many others.

There are also wild versions of some of these plants in the United States such as the black mustard which grows almost invasively in my area.

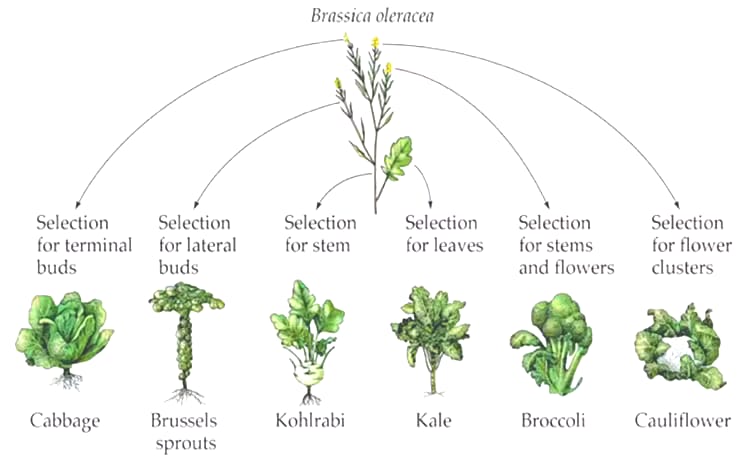

The fascinating thing to me is that so many brassicas were bred from one plant and selected for different traits into the vegetables we know today:

I’m sure you’ve seen this image before!

It’s an interesting example of how versatile a plant can be when you select over time!

Because of their versatility and the fact that they can even be perennials, I would consider them a resilient food crop that can help you eat cheaper.

History

Brassicas had a bit of a head start compared to other garden vegetables from the start; they had a lot of genetic variation before humans even domesticated the plants.

With that massive genetic advantage, it was actually very easy in the grand scheme to domesticate brassicas into so many forms. This whole group of plants seems to be prone to some level of mutation which is excellent news for us plant breeders!

The earliest example of brassica domestication I could find dates to about 2,000 B.C. in the Western Mediterranean region of Europe, but it was most likely domesticated independently in multiple places at various times.

A large-leaf heirloom kale variety called “Thousand Head”

Uses

Brassicas are generally used in cooking and fermenting. You’ve most likely had fried cabbage in Asian meals, sauerkraut, or as microgreens. Mustard comes originally from using ground brassica seeds to make a condiment!

One of my favorite brassicas to grow and eat is actually kale.

Now before you roll your eyes, hear me out: most people don’t eat kale right! If you’re using brassicas as replacements for lettuce because you hear it’s healthier then you will probably not enjoy kale.

What I recommend is to cook brassicas in stir fries, soups, and with eggs, OR to have them fresh with vinegar (balsamic especially but apple cider vinegar works well too) oil, and salt and pepper. It’s the best way to consume brassicas in a salad form!

The seeds of many brassicas are used for oils as well.

More and more I see people use ornamental brassicas these days since they withstand the cold very well and don’t wilt as quickly as other flowers do.

New kale leaves coming back the following year

Growth Habits

Brassicas are diverse and thrive in a wide range of conditions depending on species and variety. In some places, the cabbage worm, cabbage aphids, or harlequin bugs might be a lot more aggressive than in other areas.

In my climate we tend to have cabbage moths in the garden, but they never seem interested in our kale.

The only pest we ever seem to get is cabbage aphids, but we just dispose of every infested leaf and they don’t come back after the first swarm. The rest of the year we’re free to harvest as much as we like without issue!

Brassicas can be annuals, perennials, or biennials depending on the species and climate. Most people will pull their kale (biennial) at the end of the season because when it flowers it supposedly gets too bitter to eat but, in our experience, it only stays bitter while it’s in bloom. Beyond that it will go back to tasting fine.

We have two favorite varieties of kale: Thousand Head (we like the massive flat leaves) and Winterbor (A classic and our longest living kale). The Thousand Head has since been pulled because it got bent over in a storm and was growing parallel to the ground, but our Winterbor is about to go through its 6th winter, and it continues to produce an abundance of leaves year after year without any effort on my part.

We have also noticed that it will push out new leaves and roots even if it isn’t buried in the ground! After tossing some old plants in the spring, we noticed that they started sprouting only a week later while sitting on top of the compost pile. They will tolerate a lot!

Generally, if you have halfway decent soil and you mulch your kale, it’ll do just fine for you.

Wild mustard flower

Additional Information

Brassicas should be something you add to your garden for nutrition and resilience.

I mostly like the fact that they’re so much hardier than most lettuces and require less maintenance. I also love how long they produce in colder climates!

One variety of our kale (Thousand Head) starts to die back for the winter in February and then starts to sprout again in early April. That means we go a total of around 2 months or so without kale leaves!

The other thing we liked about Thousand Head was the fact that if there were insects on it, it was always very easy to see them and wash them off compared to curly-leaf kales.

In the future I will cover individual wild brassicas, but this should serve as an intro to this vast and amazing plant family.

Thousand Head Kale still green in mid-February zone 6

Cultivars

Here are some awesome varieties of various brassicas I recommend:

Thousand Head Kale - A massive flat-leaf kale

Walking Stick Kale - A tall tree collard style kale, great for a food forest

Red Russian Kale - A popular flat purple veined kale

Early Jersey Wakefield Cabbage - Short season stellar cabbage variety

Brunswick Cabbage - A large, cold hardy green cabbage

Hilton Chinese Cabbage - A classic napa cabbage selection that is easy to grow

Purple Choy Sum - A purple stalked flowering type cabbage grown for edible stems

Baby Milk Bok Choy - A small white bok choy variety

Italian Romanesco - A green fractal-head vegetable similar to cauliflower and broccoli

Old Tokyo Komatsuna - A large mild leaf mustard variety from Japan

Yod Fah Chinese Kale/Flowering broccoli - A flowering broccoli that tastes similar to asparagus

Long Island Improved Brussel Sprouts - A superior line of Brussel Sprouts

Amazing Cauliflower - An easier to grow cauliflower

Purple Of Sicily Cauliflower - An even easier and more insect resistant purple variety

Homesteader’s Kaleidescope Perennial Kale Grex - For all you landrace fans, here’s a mix of a bunch of various perennial kales

What brassica would you like me to cover next?

Follow me on social media for behind-the-scenes videos and seasonal photos!

Leave a comment to show the algorithm how legit we are!

Thanks for reading The Naturalist. Please share on social media to support the work!